AI and Preaching

Yes, I used AI to create this image. #irony

Introduction: The Insta Improvement

I was scrolling Instagram one evening when I came across a reel that crystallised a question I’d been quietly turning over for some time. It was about pastors, preaching, and AI.

A guy was describing what felt like an overnight improvement in his pastor’s preaching: the sermons suddenly had more life; sharper connections in Scripture were made that he hadn’t seen his pastor do before; and the applications that felt closer to the realities of everyday life. What had happened?

AI had happened.

The church discovered that he had secretly used AI to improve his writing – though it wasn’t a secret for long. So, the question the reel posed was simple enough: what should we think about pastors using AI to help write sermons?

The reactions, however, revealed just how loaded that question has become. Some people seemed unfazed – if the content is faithful and helpful, what is the problem? Others were deeply troubled, convinced that something essential was being lost. Even calling for pastors to be fired. Yikes!

Watching those responses, it struck me that this isn’t just a debate about a new tool. It’s a debate about preaching itself – what it is, how it forms the preacher, and what is at stake if we get this wrong. And depending on where we land, we may end up making ministry either more humane… or quietly more crushing for the people called to do it.

1. The Shrugs and Real Concerns

Okay – so what exactly are people worried about, and why?

I did a brief survey across my Facebook and Instagram pages, and the responses reflected what I suspect many Christians are feeling.

First, spiritual concerns.

A number of people worried that AI could undercut the spiritual health of a pastor – that spiritual preparation might be quietly outsourced along with sermon writing. The fear here isn’t simply about technology, but about formation: God’s Word is meant to do deep work in the preacher before it is spoken to others, and AI feels like it could short-circuit that process. If the words don’t first pass through the preacher’s own wrestling, repentance, and prayer, both speaker and hearer may be impoverished.

Second, pastoral concerns.

Others feared that sermons shaped by AI would become a façade – polished on the surface but hollow underneath. If sermons become light, thin, or generic, then discipleship will follow suit. The worry is not just about sermon quality, but about the long-term formation of God’s people.

Third, ethical concerns.

Some raised questions about bias. AI systems are trained on human material and governed by human-designed guardrails – and humans, of course, are never neutral. How might those embedded assumptions subtly shape the preacher’s words, emphasis, or even theology?

It seems fair to say that many of these concerns are not wrong. But they are often expressed with more fear than clarity.

At the same time, I noticed another reaction – a collective shrug. For many people, AI is already a familiar tool. If it helps make sermon preparation more efficient, why wouldn’t a pastor use it? Yet familiarity with a tool doesn’t automatically mean we’ve developed wise or well-thought-out principles to govern its use.

So the question remains: how should Christians – and especially pastors – think about AI and preaching without fear, guilt-inducing shame, naïveté, or shortcuts, while still taking these concerns seriously?

Before answering that, we need to be clear on what preaching actually is.

2. Let’s Think About What Preaching Is

Many of the concerns about preachers using AI seem to orbit a single fear: that a preacher could simply type, “Write me a sermon on Romans 8,” and receive something that sounds… pretty decent.

That instinct is right. Most people would be deeply uncomfortable with a preacher who, late on Saturday night, copied and pasted large sections of their sermon straight from ChatGPT. But why does that feel so wrong?

First, preaching is embodied.

It has never been merely about content. Preaching is the Word of God spoken through a real person – someone who has known real tears, real sin, pleaded real prayers, and who lives among a real community. This is why the New Testament places such weight on the character of those who teach (Titus 1; 1 Timothy 3). What is proclaimed must be carried by a life of integrity.

Character reigns over competence.

I once heard preaching described as “God’s Word through personality.” There’s something right about that. We instinctively recoil from sermons that don’t truly come from the preacher – whether through plagiarism or performance – because they haven’t been embodied. They haven’t passed through a life.

Second, preaching is formed over time.

Some of the most encouraging words I’ve received recently came from an older saint who said, “I’ve seen you grow in your preaching over the years.” This from someone who has listened to me as a lay preacher, a ministry trainee, a theological student, and then stumbling through sermons as a young (and overly enthusiastic) pastor.

Preachers grow through average sermons, bad sermons, and the occasional sermon that’s hit for four – and rarer still, six (cricket fans will understand). They grow through feedback, critique, encouragement, and through their own slow maturation as disciples. Over time, all of that is poured into their preaching.

AI can construct something that is true enough. But it hasn’t been passed through a growing heart, through the experience of failure and learning, through counselling sessions, hospital visits, Bible studies, staff meetings, and the ordinary, hidden work of pastoral ministry.

So – does this mean AI is simply off-limits for preachers?

Not quite.

If preaching is embodied, cumulative, and deeply human, then the way a sermon is prepared matters. So, before saying anything about how AI is incorporated into my process, it’s worth briefly explaining how I approach sermon preparation in the first place.

3. My Sermon Preparation Method

If you’ve ever wondered how a sermon comes into being, you’re not alone. I suspect many people imagine something fairly straightforward: the preacher reads the passage, prays, opens a blank document, and starts writing.

Let me open my office door and invite you into the adventure of what actually happens – at least on a good week.

It usually begins on Monday morning, with a text already waiting for me. Our preaching calendar is planned in advance, so the passage for Sunday is fixed. There’s no last-minute scrambling for a topic – just the quiet weight of a text that will not let me go.

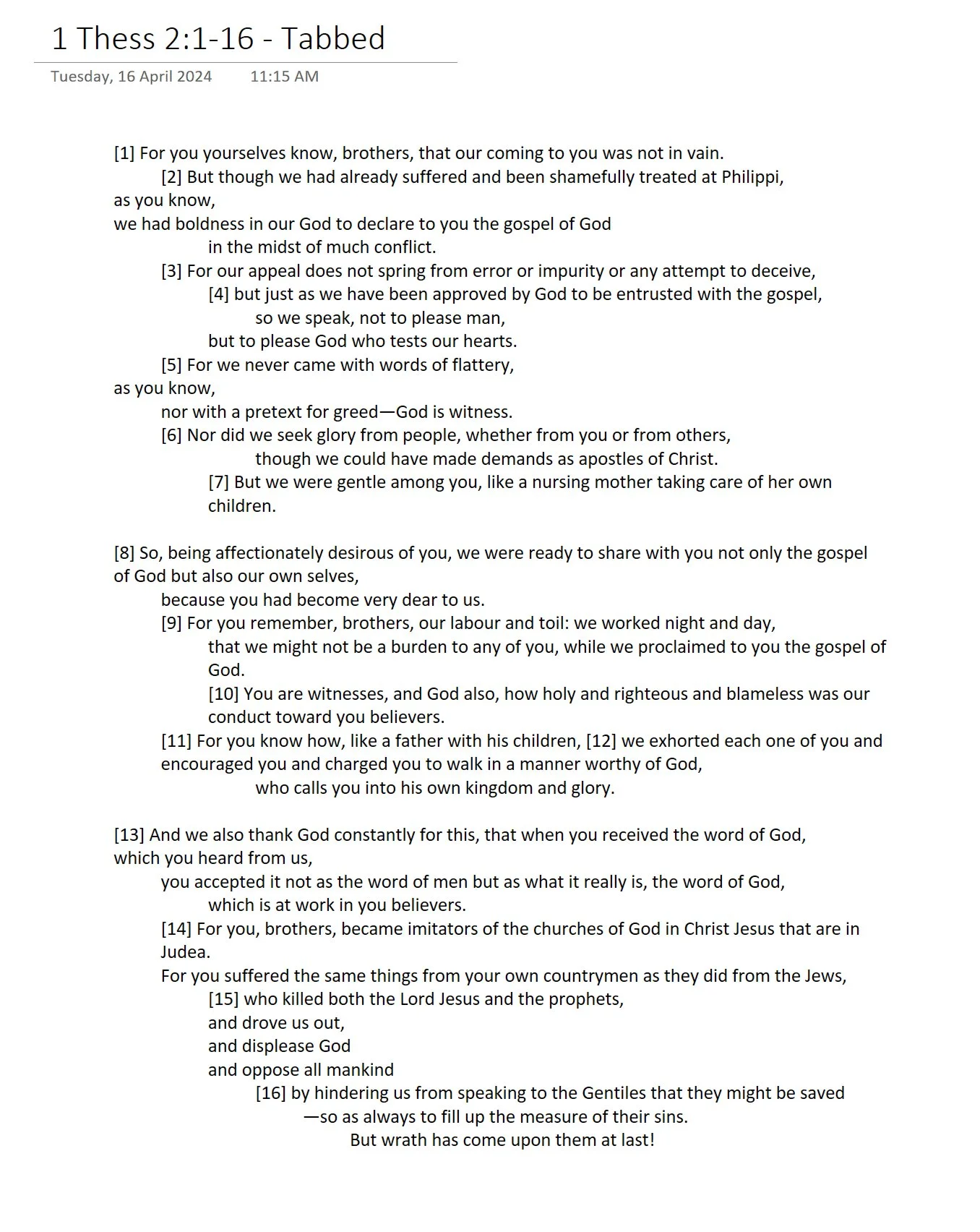

Here’s where I begin - copying and pasting the ESV text. I also change all the annoying American spelling into English spelling!

I pray. Then I copy the passage – ESV – into a Word document and read it slowly. Once. Twice. Sometimes more. I widen the lens and read what comes before and after, trying to feel the contours of the argument. Where does it rise? Where does it turn? Where does it land?

Then I start pulling the passage apart.

I use a method something like text-tabbing – breaking the text down visually, hunting for the main verbs, tracing how each clause leans on another. It’s less about nailing syntax and more about learning how the author is thinking. I want to see the passage before I say anything about it.

This text-tabbing method I was shown a few years ago - I’m working on the passage in a way that breaks the sentences down in a way that helps me see the structure, points made, and what subpoints are made. It helps me visualise the passage and hone in on the main subject, point and purpose of the passage.

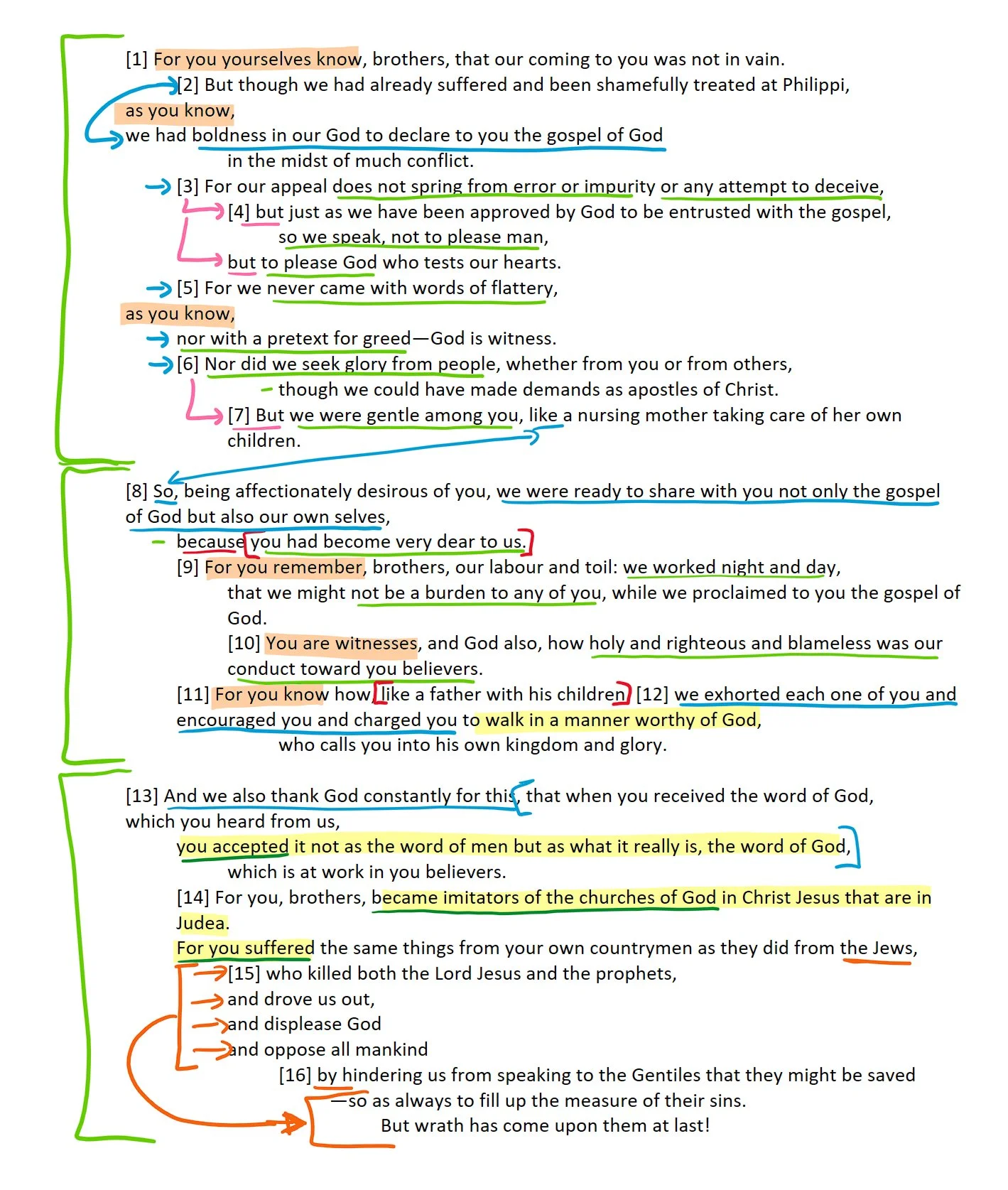

Once that’s done, I print it.

Out come the analogue highlighters and pens. I mark repetitions. I underline phrases that seem to carry weight. In blue, I circle the parts I don’t yet understand – awkward wording, strange logic, phrases that refuse to resolve. Those blue circles are important: they’re the places I know I’ll need to slow down later, look things up, and ask better questions.

Here’s an older digital copy of what I do with pen and paper now, where you can see the highlighted and marked-up text - I’m working out what links where, what are the natural movements in the passage, what imperatives are clear (applications), and anything I’m not certain about.

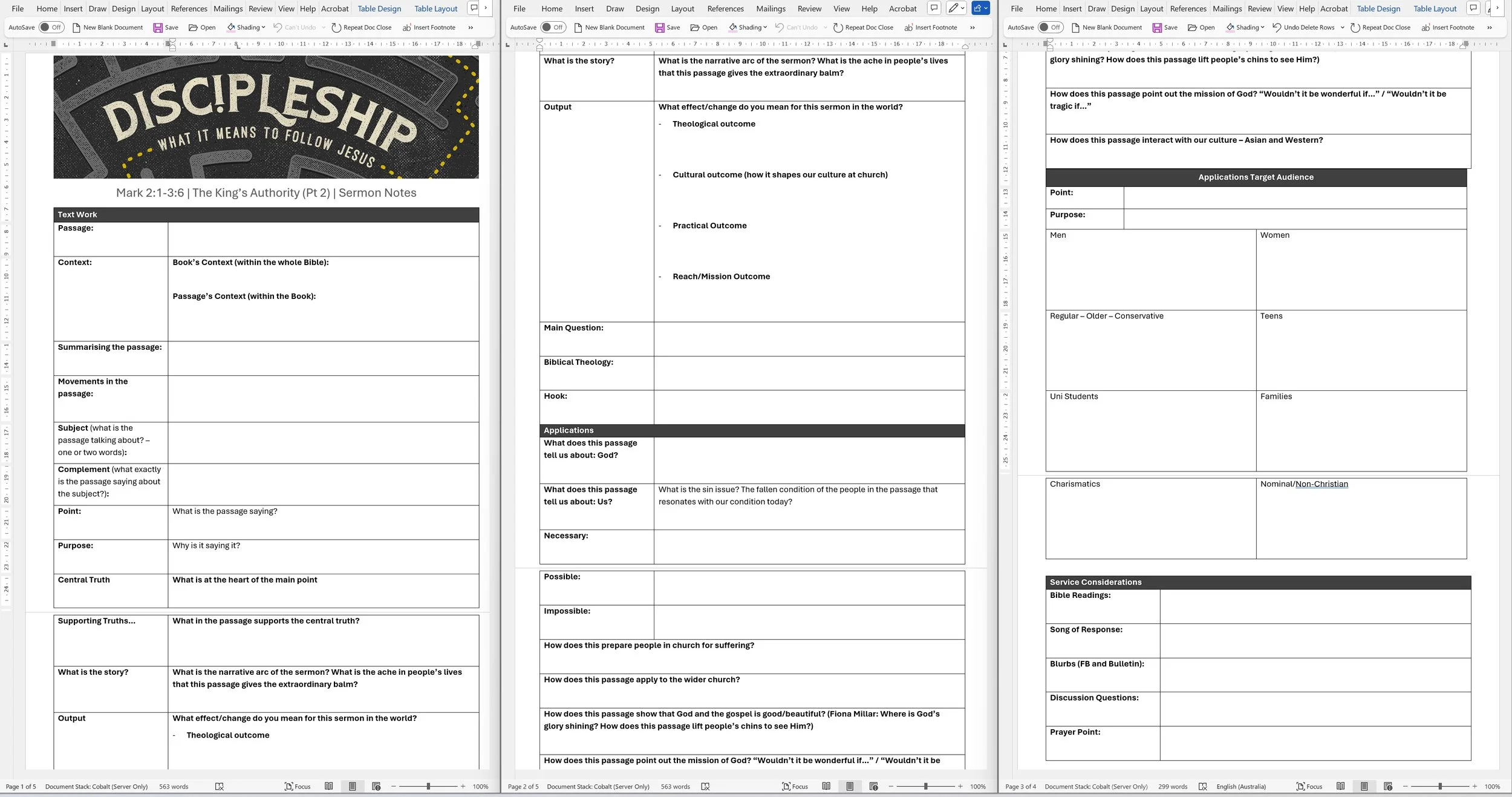

Only then do I open my sermon notes document.

My Sermon Notes document is pretty extensive and asks heaps of questions about the passage and heaps of application questions. It’s designed to slow me down and help me think through the passage and sermon.

The first task is deceptively simple: What is this passage actually about?

Not every theme. Not every implication. The main subject. From there, I work out the complements – what the passage is saying about that subject. Sometimes there are multiple subject candidates, and the work is in testing which one best accounts for the whole text. That means exegetical work: grammar, flow, and logic – not vibes.

From there, I try to articulate the main point and purpose. What is the passage saying? And why is it saying it? This isn’t a summary; it’s a synthesis – a single, weight-bearing sentence that captures the author’s intent.

That sentence gets reworked. A lot.

Can I explain it simply?

Could a teenager grasp it?

Can it be repeated and reinforced throughout the sermon?

Then comes application – the longest stretch of the journey.

What does this passage show us about God? About us? What applications are necessary? Which are possible? Which would be illegitimate? How does this speak into suffering? Where does it lift our chins up to see God’s grace and glory? How does it land differently for teenagers, parents, retirees, weary believers, and those still exploring faith?

Only after all of that do I begin outlining the sermon. The exegetical movements are placed. Illustrations are worked in. Applications are threaded throughout. The aim is movement – not just explanation – building toward a final, weighty moment of address.

By the time Wednesday ends, I’m usually spent. Thursday is a sabbath day. And on Friday, with the notes and outline spread out in front of me, I write. A word for word full manuscript.

One final thing matters here: None of this began with AI.

AI didn’t invent this process. It has been shaped slowly, over years, through preaching, feedback, mistakes, growth, and grace.

4. How I use AI in Sermon Preparation

As you can see, my sermon preparation process is lengthy – and, by modern standards, somewhat inefficient. It slows me down considerably and I’ve come to see that as a feature, not a bug.

Especially having recognised in recent months that I carry many ADHD traits, I need this kind of process. It forces me to slow down. And slowing down helps me think. It helps me engage the text not just intellectually, but with my whole being.

What might look like inefficiency on paper is, in reality, a long journey into the passage, into my own heart, and into the hearts of the people God has entrusted me to shepherd and guide.

So where does AI fit into that process?

For me, it comes in on Wednesday afternoon or evening.

By that point, I’m not asking ChatGPT to tell me what the passage means. I’ve already spent several days wrestling with the text myself. AI enters late, and in limited ways.

First, I use AI to test faithfulness to the text.

I’ll run my subject and main point/purpose past ChatGPT, not to receive answers, but to pressure-test my work. At its best, AI functions as a sparring partner – helping me see whether my conclusions genuinely account for the passage as a whole.

I’ll also test whether my applications are truly tethered to the text and whether they speak to the heart rather than floating free of the passage. Occasionally, I might share an early outline and ask whether there are alternative ways of framing or ordering the material.

It’s important to say that I don’t accept these suggestions wholesale. In fact, I’ve often found that AI tends to drain colour from my preaching – flattening phrasing, removing repetition, and shortening stories more than I’d like. I’m constantly engaging, resisting, refining, and sometimes ignoring its suggestions altogether.

Second, I use AI to test structure and pacing.

Over the years I’ve noticed a tendency to overload my first one or two sermon points, often at the expense of what follows. AI has been helpful in highlighting where early sections carry too much weight or detail, and where the sermon’s overall movement may stall.

As I write, I might occasionally ask AI to help smooth wording or suggest alternative phrasings. But the words are always poured over and prayed over. They remain my words – even if some were shaped through a prompt.

Third, I use AI to test my own instincts as a preacher.

Over time, I’ve become aware of certain patterns in my preaching – a tendency to over-explain, to lean too heavily on pastoral experience rather than the text, or to let dense theology crowd out emotional movement. At times, AI has helped expose those patterns.

I’ll ask questions like: Where does this feel heavy? Where might listeners lose the thread? Does this sound more like explanation than proclamation? Is the tone matching the weight of the passage? In that sense, AI functions as a kind of proxy listener – not replacing real people, but helping me notice where clarity, warmth, or movement might be lacking.

One thing I’m careful to say plainly: I don’t use AI to hear from God.

I don’t look to it for insight, conviction, or spiritual authority. That work belongs to God’s Spirit through God’s Word. AI may help me refine language or notice weaknesses, but it has no place in illumination, repentance, or revelation.

Ultimately, I keep returning to a simple test, helpfully articulated by Stephen Driscoll: Could I preach this sermon without AI’s help?

If the answer is yes, then AI is seasoning – something that makes everything sing.

If the answer is no, then AI has become the main dish, and I’m just the seasoning.

And that’s a line I don’t want to cross.

5. The dangers and “dangers” of AI and preaching

Which leads naturally to a question we do need to face honestly: what are the real dangers of preachers using AI?

As I’ve grown in my own experience of using AI in sermon preparation, I’ve become more aware of the genuine risks it presents – concerns that have been echoed in articles, podcasts, and workshops I’ve engaged with. Some dangers are real and serious. Others are probably overstated.

Let’s begin with the real ones.

1. AI shortcuts thinking

The most significant danger, and the one I feel most keenly, is that AI can shortcut thinking.

Writing is thinking.

Contrary to how we often imagine the process, sermons don’t emerge fully formed in the mind and then simply get written down. Thought is clarified, sharpened, and sometimes even discovered through writing. AI threatens to bypass that process entirely. It can produce language instantly – with clarity and eloquence that often exceeds the average preacher – and in doing so, it can quietly replace the slow, demanding work of thinking.

But losing our thinking is no small thing. To lose the discipline of thinking through God’s Word is to lose a crucial part of pastoral ministry itself. Ministry requires meditation, reflection, and sustained attention – allowing Scripture to dwell richly in us as we live, move, and minister among God’s people.

Lose that, and we lose the engine block of ministry.

2. AI shortcuts formation over time

Closely related to this is another danger: AI can shortcut growth.

Preaching maturity is slow. Painfully slow. There’s a particular ache in being an average preacher – pouring yourself into a sermon only to realise, through feedback or reflection, just how much there is still to learn. Most growth happens through ordinary sermons, weak sermons, and the occasional sermon that almost works.

That process takes years – even decades.

What AI offers is the temptation to perform better more quickly, without necessarily understanding why. It can accelerate output without deepening wisdom. And if that happens, performance can begin to outpace formation.

Preaching, however, is meant to grow alongside the preacher. Over time, a life lived under the Word – with all its failures, pastoral encounters, and slow lessons – shapes what and how we preach. AI cannot replicate that formation, no matter how polished the language it produces.

3. AI risks trust and reputation

A third danger concerns trust.

Here, Stephen Driscoll’s reflections on plagiarism are helpful: the proportion of material copied, the purpose behind copying, and how personal the message is all matter. The more a sermon relies on copying and pasting – especially in ways that obscure authorship – the more credibility is eroded. And once trust with hearers is lost, it is difficult to regain.

Those are real dangers. They deserve to be taken seriously.

But not every concern raised about AI belongs in those categories.

Some concerns that are often overstated

Ethical bias.

Yes, AI systems are trained on human material and governed by human-designed guardrails. Bias exists. But bias has always existed. Every commentary, search engine, and theological resource carries assumptions. This is where pastoral discernment – shaped by theological training and years of ministry – must continue to be exercised. AI doesn’t remove the need for discernment; it heightens it.

Shallow sermons.

There is a fear that AI will inevitably produce thin, generic preaching. But shallow sermons are not caused by tools; they are caused by shallow preparation. Used as a copy-and-paste generator, AI will hollow sermons out. Used as a sparring partner, it can expose weak thinking rather than create it. ChatGPT does not know a congregation, a context, or a pastor’s heart – and it never will.

Spiritual harm.

This concern is real – especially if AI is introduced too early in the process. In an already crowded pastoral week, AI can tempt us to bypass prayerful wrestling with Scripture. This is why timing and discipline matter. When used late, and carefully, AI need not undercut spiritual health. When used early or indiscriminately, it very well might.

Which is why clear guardrails matter.

6. A Couple of AI Rules

Which brings me to the guardrails I’ve put in place for myself. These aren’t Ten Commandments – but they are commitments I’m trying to hold consistently.

Pen, Paper, Personal Processing – then the Plugin

I’ve committed to beginning with Scripture, not AI. I want the text to confront me before I ask for help in bringing it before others.

To guard against shortcutting my thinking, my sermon preparation is intentionally slow. Inefficient, even. While AI could certainly make things faster – freeing up hours for other tasks – that efficiency comes at a cost. The inefficiency of ministry is not accidental; it is deeply human and deeply necessary.

It is in the struggle for words, the wrestling with meaning, and the slow articulation of ideas that I am personally shaped. Only after that work has been done do I invite AI into the process. That order matters. Without it, sermons risk becoming polished but performative rather than personal and pastoral.

Transparency about where ideas come from

Clarity builds trust. And right now, there is no shortage of suspicion around AI.

Part of the reason I’ve written this post is to name openly how I use AI in my preaching. But ongoing transparency matters too. When I say, “I looked this up on Google,” no one bats an eye. When I say, “I asked ChatGPT to help me think this through,” people are understandably more cautious.

That may simply be because AI is new. Or because we’re still learning how to place it properly. Either way, I want to be clear with my congregation about the tools I use – not because they replace the work of preaching, but because they serve it.

Even with these commitments in place, I’m aware that they don’t answer every question. Some of the implications of AI – especially over time – are still emerging. So before finishing, I want to name a few questions I’m still wrestling with.

7. Questions I’m Still Wrestling With

These aren’t objections to using AI, but areas where I’m intentionally staying alert.

How is AI shaping my voice over time?

How much is AI adapting itself to my tone and patterns, and how much am I being subtly shaped in return? I suspect it’s both. And that may not be inherently bad – we are always shaped by what we read, hear, and absorb – but it is something worth watching carefully.

How do we remain meaningfully human in an AI-saturated world?

As AI-generated content becomes more pervasive – and more convincing – I worry that it may quietly reshape our expectations of what is “normal.” A world that prizes polish and performance can make ordinary, slow, imperfect human growth feel inadequate. What will it mean to be average, to learn slowly, and to grow over time in that environment?

How will these practices need to change as the technology evolves?

AI has advanced at a staggering pace. Will it plateau? Or will new capabilities introduce new pressures and temptations? If so, how might the commitments I’ve outlined need to be revised or strengthened in the years ahead?

These are questions I’m still thinking through. For now, I’m trying to remain both open-eyed and grounded – grateful for the help AI can offer, while determined not to outsource the slow, formative work that preaching requires.

Conclusion

With some further help from Stephen Driscoll’s work, a few concluding reflections.

AI is here to stay. That much seems unavoidable. It is already being woven into almost every part of life, and ministry will need to learn how to minister faithfully in an AI-shaped world. Even if pastors choose not to use AI personally, many around them already are – staff members, ministry trainees, Bible study leaders, and lay members alike. Like every major technological shift before it, wisdom will not come from either blind adoption or fearful rejection, but from careful, principled use.

And while AI represents a significant change, it is not the first. God’s people have always lived and ministered amid technological transitions – from scrolls to codices (books), from horse and cart to car, from radio to photocopiers to the internet. Each shift has required reflection, discernment, and restraint. AI is no different.

There are real benefits here, and real dangers too, with plenty of complexity in between. The task before us is to wade through thoughtfully – neither baptising the technology as a saviour, nor treating it as a threat to be exorcised.

At the same time, we find ourselves in a world increasingly saturated with AI slop – in both written and visual forms – content that is fast, polished, and increasingly impressive, but often hollow. And into that world, the church continues to offer something utterly different and deeply remarkable: not more artificial intelligence polished lives, but the Creator himself entering the world, to forgive and reconcile through his blood, so that we might enjoy Divine and Personal Intelligence for eternity.

And that is the preacher’s irreplaceable task.

Which leads to a gentle but important word, especially for younger preachers.

There are no shortcuts to faithful preaching. Growth takes time. Formation cannot be rushed. AI may help refine expression, but it cannot substitute for the slow work of living under God’s Word – being shaped through ordinary sermons, honest feedback, pastoral joys, and painful failures. Beware the temptation to sound like you’ve arrived before you’ve been formed. Let your preaching grow at the pace of your discipleship.

Because in the end, the preacher’s task cannot be automated. It is to stand before God’s people with God’s Word, having first been confronted, comforted, and changed by it themselves – and to proclaim, week by week, not a polished performance, but the living Christ.

And that is something no machine can replace.